Collective Sends over Individual Projects

I’ve structured much of the last few years around a long term goal of becoming a Certified AMGA Rock Guide. Every fall and spring, I’ve headed to Red Rock Canyon to train on the endless multi-pitch routes found outside the Las Vegas suburbs. Friends have flown down or driven out to help me practice, following me up pitch after pitch and spending blustery nights in the notoriously windy Red Rock campground. Last fall, I completed a big step in the process, passing the Advanced Rock Guide Course and Aspirant Exam, which includes ten days of instruction and examination on multi-pitch terrain.

Now, in this post-election moment of reflection, this goal is starting to feel almost like a distraction. I’m pretty close to reaching it; I’ve finished all but a few of the prerequisites required before taking the final, six day exam. Certification is a concrete achievement that’s within reach, which feels good in this period of uncertainty and collective anxiety. But I wonder if part of the appeal of this goal is a sense of control amidst cascading societal issues that feel impossible to solve. I also wonder if the tangible pursuit of individual achievement distracts me from collective action around overwhelming crises like climate change, income inequality, and human rights abuses.

On a training trip in Red Rock Canyon

Climbing as a container for learning life skills

For most of my career, I’ve looked for ways to transfer the lessons we learn from climbing or other outdoor activities to our daily lives. I spent many years leading backpacking trips for youth, with goals of developing leadership skills, building community, and encouraging self reflection in young people. We would often start with a goal setting session, making “S.M.A.R.T.” goals that were specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and timely. We hoped that going through this process in the backcountry would translate to their goals at school, on their sports teams, and in their broader communities.

Later, as a youth climbing team coach, I had countless discussions with other coaches about how competitive climbing can be a container for learning essential life skills. We used the framework of training for competitions to teach young people about breaking down larger end goals into smaller process goals, about how progress happens when you show up consistently, and about the importance of failure in the learning process. We also worked to create a culture that recognized effort over results and curiosity over podiums.

I’ve used a similar process to work toward my rock guide certification. When I first got curious about this end goal, I decided I would commit to the process of preparing for the next step and see how it felt. I started working on the prerequisites for the next level guide course, focusing on smaller goals that added up toward the big end goal. And it worked! After putting training trips on the calendar and following through for almost two years, I successfully completed a major step in the process by passing the Advanced Rock Guide course.

Sometimes you need collective support for your individual send!

The opportunity cost of sending our projects

It felt really good to check that box, and it left me hungry to check the next, which would be the exam. I have been completing prerequisite climbs, ticking them off a list over the course of the last year. It feels good to cross them off, like items on a “to-do” list, tangible steps in the process toward the big end goal. That sense of control, I think, is part of the appeal, especially during a chaotic time. In Naomi Klein’s recent book Doppleganger, she explores how efforts to perfect the self, build our personal brands, and optimize our children obscure the collective crises of our time. Reflecting on this pursuit in her own life and yoga practice, she says “I couldn’t stop the U.S. invasion of Iraq – though millions of us tried like hell – but I could coax my body into Crow Pose and, on a very good day, do a handstand.” (p. 173)

I do still believe that climbing can be a container to learn life lessons and build community. But the problem is, our end goals often begin and end with climbing. Focusing solely on a climbing project — or rock guide exam — reinforces self discipline over collective action. ‘If I can just stick to my training schedule and nutrition, I’ll achieve x, y, or z goals.’ This also isn’t unique to this sport; our focus might be a personal finance goal or house project or work promotion, with our efforts beginning and ending at the level of the individual. As I look toward completing the rock guide certification, I’m pausing to ask myself why. What is gained, and what is the opportunity cost? What is losing my attention as I structure my year around honing this craft?

Professional climber Katie Lambert acknowledges these opportunity costs in her Climbing Magazine essay, “What’s the Point of Climbing?” Returning from a three month trip to Spain, she reflects on the accomplishments of her husband Ben Ditto during the trip, saying “he kept his nose to the grindstone and did the work, despite doubts or uncertainties.” Having made climbing a way of life for decades, Lambert is familiar with the community sacrifices needed to send hard grades. She acknowledges that it may mean “missing out on family time because your schedule is based on good conditions or perfect temps, not cultural or family traditions.”

This is not to say it’s wrong to pursue individual goals - of course not! But I’m pausing to ask whether my individual pursuits are distracting me from participating in the collective action needed to solve other issues I care about. Klein says further, “As the climate crisis accelerates, with the land heaving beneath us and burning around us, I expect that many of us will continue to find solace in whatever small bodily obeyances we can muster. There is solace there.” (Doppleganger, p. 173) As I pursue harder grades or heavier deadlifts, am I ignoring the squishier but critical problems that have less obvious process goals and impossibly out of reach end goals?

I hope my community members who are also going through the certification process don’t read this as a critique of their successes. Lots of my friends just passed their final rock guide exam, and I am super proud of them! Some have already offered mentorship to others, and some were motivated to complete this step so they could create affinity spaces for aspiring guides. Other friends who have completed certifications have found ways to offer scholarships and sliding scale pricing for advanced climbing courses, further decreasing barriers to the sport and building community.

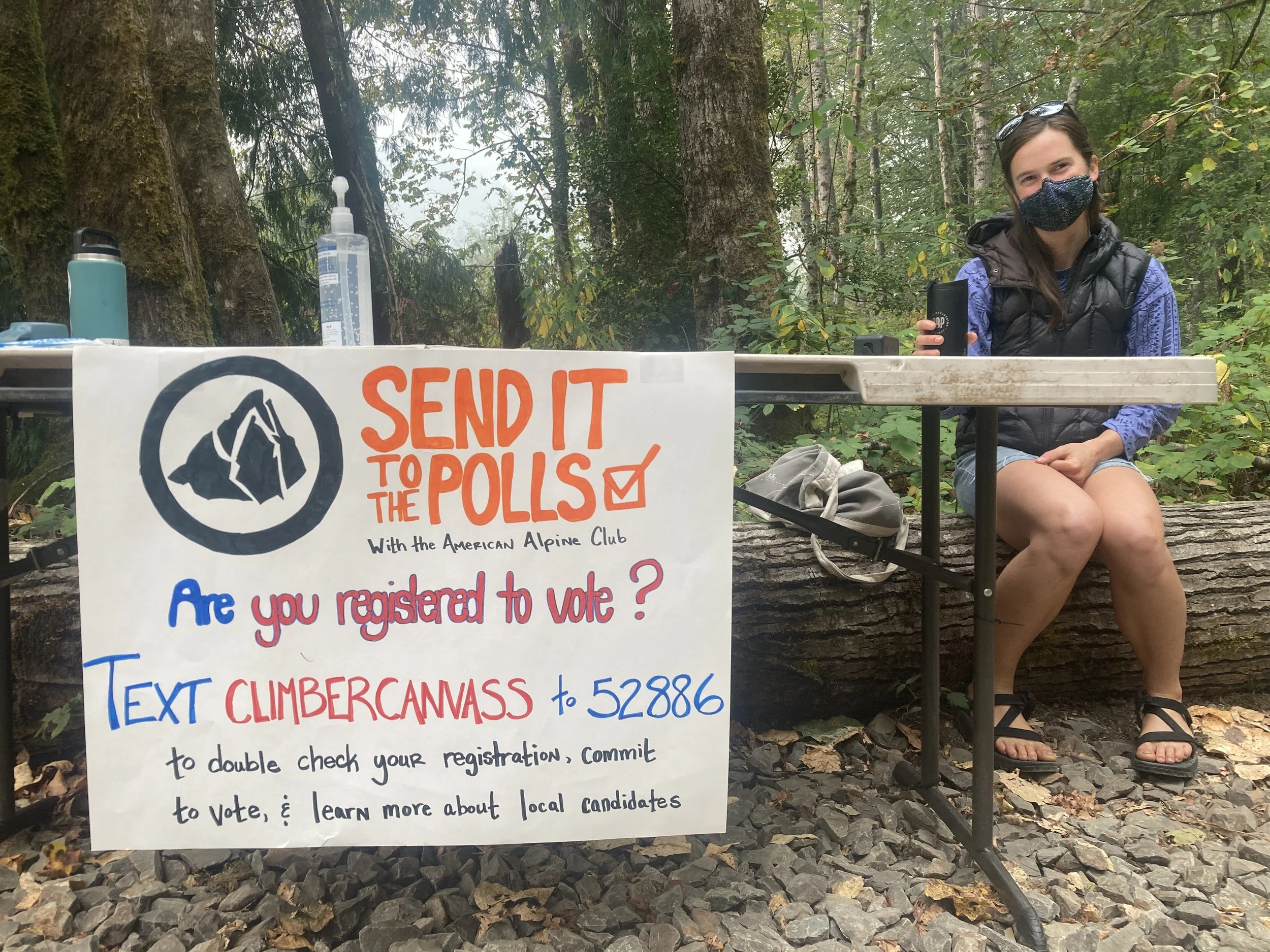

Finding ways to motivate collective action through climbing in 2020.

Refocusing Our Collective Attention

I also believe that there are avenues within climbing for collective action, and I do see members of my community harnessing those opportunities. The climbing community is just that – a community, however fragmented at times. Existing connections within gyms, at crags, in online forums, and professional guide organizations can be built on to address bigger problems, and sometimes they are. Climbing can also be an important source of community healing and joy, as it has been for Palestinian climbers in the West Bank during Israeli apartheid and the horrific assault on Gaza.

Climbers across the world came together last spring to raise money for the humanitarian crisis in Gaza and raise awareness of the Israeli apartheid walls through a global Climb-a-thon. Climbers joined with Indigenous nations and conservationists in the fight to protect Bears Ears National Monument. While she does direct a great deal of attention toward sending hard routes, pro climber Katie Lambert also helps lead a program called Sacred Rok, which helps local, underserved youth connect to themselves and the natural world through climbing and other outdoor activities. Maybe there is space for individual goals and collective action within climbing, if we seek balance with intention.

Climbing still has life lessons for this moment, when it feels like there are so many different fires to put out. A mental training concept developed by Arno Ilgner of The Rock Warrior’s Way offers a method for mindfully directing our attention that could be applied to movement work as well as sending our projects. Ilgner divides up climbs between stopping points and moving between these stances. A stopping point provides a chance to “recover energy and to do the necessary thinking about what lies ahead.” This is the time to analyze risks and make a plan for moving forward. After gathering information, the next step is moving with the body, fully committing and staying grounded in the present moment until reaching the next stopping point.

In a time with overlapping crises, it’s easy for our attention to be fragmented, with our actions reduced to shouting on social media. I know I fall into this trap. What if instead we stopped to analyze the problems and reflect on our strengths, as Ilgner coaches? Ocean scientist and climate communicator Dr. Ayana Elizabeth Johnson offers us a framework for this process with her Climate Action Venn Diagrams model. Then, once we’ve identified the action that harnesses our talents and resources, we fully commit to our next step within collective solutions. In the same way that we break down a larger climb into rest stances and crux sequences, we can break the crises of our time into smaller actions, with each of us contributing our individual gifts to collective liberation.

Climbing skills as a climate solution! Glacier monitoring on Mount Baker / Kulshan.