Tied Into Place

How my local crags connect me with community as “third places.”

When I lived in cities, I had plenty of ‘third places.’ The first one I remember regularly frequenting was a coffee shop called Nina’s a few blocks from my childhood home in Saint Paul, Minnesota. I used to go there to study for finals during high school when I couldn’t focus at home. During one study session, a barista gave me a sticker to let me know she was cheering me on amidst my piles of books and papers. My friends and I used to meet there to play Speed Scrabble and drink chai lattes; we were pretty wholesome teenagers.

Coffee shops, neighborhood bars, rec centers, and libraries have all filled my need for third places throughout my life. A term originally coined by sociologist Ray Oldenburg, a third place is a place you go that’s not work or home. Sometimes referred to as the “living room of society,” they are physical locations where we might meet friends, bump into acquaintances, or connect with strangers over informal conversation. Third places help us feel a sense of connection to a larger community, even through casual relationships.

As an adult living in Seattle, the climbing gym became my second and third place. For several years, I coached a youth team at a bouldering gym in the south end of the city. I would regularly spend ten to twelve hours a day there, climbing with friends, lifting weights, working in the office, coaching, or grabbing a beer after work in the downstairs bar and staying for a round of trivia. My connections there spanned from close friends to co-workers to parents of the climbers I coached to strangers who recognized me as the lady who crowded the walls with kids after school.

The 8th Anniversary Party at the climbing gym where I worked

During those years, I remember feeling a sense of being held by the community and showing up for it in return. When I needed a new place to live, I was introduced to friends of a friend who had just built out a basement unit in their house. When my bike was my primary mode of transportation, multiple friends loaned me their cars while they were on extended trips abroad. When a member of my community whom I’d only met once passed away, I helped make phone calls to people who cared about him, so they wouldn’t have to find out on social media.

When the pandemic started and I left the city, I noticed I lost particular types of relationships, ones I started calling “third tier friends.” You know those people that you’re always happy to run into, but you wouldn’t call personally to make plans? Those were the relationships decimated by covid. Third places aren’t always filled with your best friends; they are characterized by informal, non-intimate conversation and connection. Studies have shown the surprising power of weak social ties on our well-being. Though I kept up with close friends on the phone or through outdoor hangs, my sense of belonging to a larger community was stripped away.

My very last day of coaching was March 1st, 2020, just a couple weeks before the whole gym shut down due to covid-19.

Redefining My Third Places

The first couple times that I distinctly remember trying to learn how to hand-jam were on crack climbs in Index and Joshua Tree. Both attempts were back in 2015, which is also the year I fell head over heels in love with trad climbing. That summer, I flailed my way up Toxic Shock, a 5.9 thin hands crack at Index’s Inner Walls. It was my first visit to this old granite quarry next to the sleepy little mining town. I could barely move the next day after struggling up the steep walls.

Later that fall, I went on my inaugural desert road trip, learning to “dirtbag” in a 2002 manual hybrid Honda Civic that I borrowed from a friend. He taught me how to drive stick shift during a 45 minute lesson in a Seattle parking lot, then left his car with me for six months while he traveled to Ecuador. After some trial by fire while attempting to drive uphill during rush hour in Seattle, I headed south. I spent the first half of December that year in Joshua Tree, where I tore open the back of my hand and got my first gobi on the steep direct start of Mike’s Books.

An early trad lead on my first trip to Joshua Tree in 2015 getting scared on sandbagged 5.6 "Leaping Leaner."

Fast forward nine years, and I now call both of these places home, traveling seasonally between Index and Joshua Tree while working year-round as a climbing guide. When I was rooted in Seattle, my local crags were places I went on the weekends to go rock climbing. More recently I’ve realized they’ve become much more. As I lost my indoor third places due to the pandemic, I’ve started to depend on my connections to these outdoor spaces for that same sense of belonging and connection to community.

The Gunsmoke Traverse or the Lower Town Walls now feel like my neighborhood coffee shops. They’re places I go to catch up with a friend over a few fitness laps. I run into old co-workers or team kids that I used to coach – not really kids anymore – cruising hard routes at the Lower Town Wall. I make new friends by offering a padstack or beta for the crux of Gunsmoke. During the winter in Joshua Tree, Gunsmoke gets the last light of the day, so it holds warmth as the sun sets over the desert. It’s the best place to go after a day of guiding in the park, so you’re bound to run into friends or meet other locals.

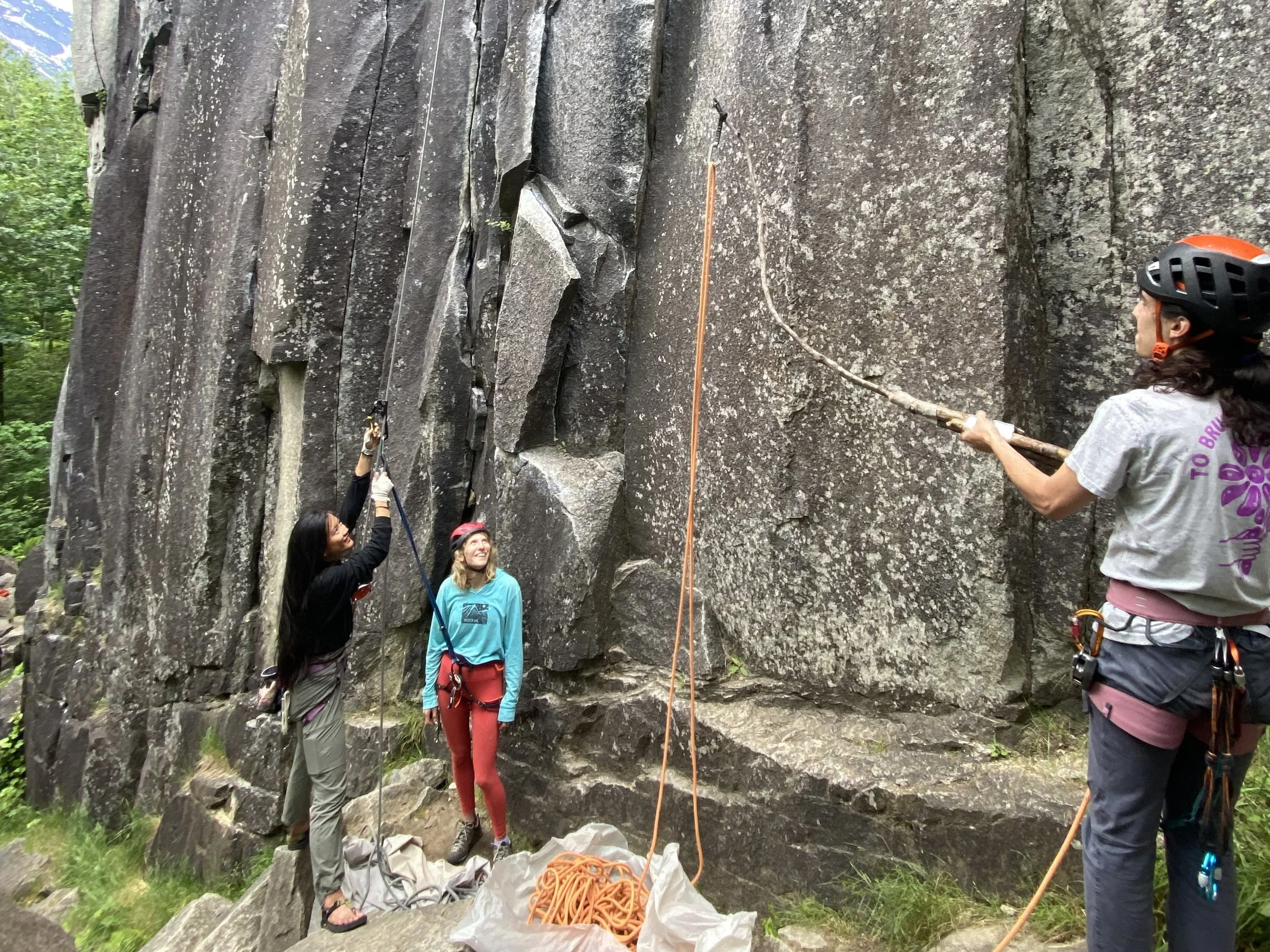

"Stick" clipping shenanigans on Lower Town Wall classic "Tatoosh."

Crags of Collective Memories

I’ve spent so much time in both of these areas over the last decade, that every individual wall feels like a container for the story of my life. Returning to different crags brings back memories with dear friends, big sends and big failures, and past relationships and seasons of life. Walking by previously unnoticed lines sparks new goals and dreams, as I evolve within these spaces.

I first met my now partner top-roping at the Lower Town Wall; we felt a spark, then made plans to climb again later that month. On our first date, we decided to climb at The Cheeks, a steep wall accessed by an obstacle course of fixed lines, rebar ladders, and a via ferrata. Distracted by my crush, I blindly followed him on the approach, which was fuzzy in his mind at best. We ended up losing the way and bushwacking up steep, mossy forest before finally stumbling on the “Perverse Traverse” that leads to the base of the Zipper. Every time I return I smile at the memory of our new relationship, now over five years old.

By returning to these physical places, I have a marker for where I’ve been and how I’ve evolved mentally and physically. I used to be terrified of climbing in Joshua Tree, when I was just an infrequent visitor. I traveled there during the fall of 2019 for a Rock Guide Course with the American Mountain Guides Association. When my boyfriend picked me up at the airport, I was shaking with performance anxiety, thinking about the runouts and bold climbing I’d have to do to pass the course. I didn’t end up passing on my first try, having come into the course with a shoulder injury that also served as a convenient excuse to avoid harder leads.

Photo from my Rock Guide Course in Joshua Tree in 2019

Four months later I moved to Joshua Tree, partly by accident, as the pandemic raged across the country and shut down our communities. I never thought I’d find a home in the desert, but I just keep returning every fall. My relationship with the place deepens every year, and my mental capacity has grown. I’ve fiddled in hundreds of cam placements, smeared on every angle of monzogranite, and know which routes to approach with caution and which are good for pushing my limit. Five years after my anxiety-ridden AMGA course, I confidently guide routes at much harder grades.

I’m not unique in these experiences. These walls hold the collective memories of our communities, uniting us in our connection to place. They contain pain as well as joy, as we play out our lives amidst these granite walls. As I scramble over boulders or climb up via ferrata rungs to crags in the forest, ghosts of injury and trauma as well as connections and successes float by. Sometimes I feel like these crags are like rooms in my house, as I host friends and family members for climbing days or I run into co-workers on my way back to the parking lot.

Sharing the Gunsmoke Traverse with friends from the gym - new and old third spaces collide!

Mutual Relationships With Place

I always feel like I should plan more climbing trips to far off destinations, like somehow I’m lacking as a person or climber because I’ve done very little international travel. But I’m becoming less embarrassed to admit that I like returning to these places year after year. It’s not just the memories I have with people at these crags, but the relationships I’ve developed with the places themselves. As a climbing community, we often pedestalize collecting far flung adventures, but I’m starting to place a higher value on deep knowledge of fewer places.

Another essay about third places suggests that the physical attributes of a place also contribute to its social value. In Joshua Tree and Index, I know how the friction of the granite varies at different crags. I can tell you how the sun-shade timing changes at dozens of walls in Joshua Tree from fall to spring. I know which finger cracks are also homes for lizards and where you might wake up a sleeping bat in a hand crack. I’ve learned, through trial and error, when the NOAA forecast that calls for a slight chance of showers actually means perfect conditions in Index during early summer.

The more deeply we know a place, the better we can take care of it. We’ll be able to kindly inform visitors that the scent of their dog’s pee may scare bighorn sheep away from their annual watering holes or donate time and money to rebolting efforts. We’ll be more likely to offer up our retired ropes and replace the ratty fixed lines strewn around the Index Town Walls. The relationship is mutual; I feel cared for and held by these physical places and the community they attract. I can only hope that I care for them enough in return.

Doing what I love in my favorite place!